The Danger of Low-Hanging Fruit: Managing the "Unknowns" in Engineering

The Danger of Low-Hanging Fruit: Managing the "Unknowns" in Engineering

As engineers and project managers, we should be familiar with risk and mitigation strategies because we will undoubtedly encounter known unknowns and the dreaded unknown unknowns. The ability to plan and mitigate these technical challenges will ensure we can effectively execute and meet expectations. Gravitating to the easier tasks or the “low-hanging fruit” instead of tackling the tasks with uncertainty is a trap engineers need to avoid.

The Origins of Uncertainty

The term unknown unknown sounds like an exercise in logic or philosophy. Its birth is hard to trace, but some think it may be derived from the Johari Window model developed by Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham in 1955. This tool was developed for interpersonal awareness and utilized a four-quadrant model categorizing what is known to self/known to others, known to self/unknown to others, unknown to self/known to others, and unknown to self/unknown to others. Another source might be from the 1950s and 1960s development of PERT (Program Evaluation and Review Technique) by the U.S. Navy for the Polaris missile program. It contained one of the first formal acknowledgements of uncertainty or “risk” in projects. The concept of “Black Swan” events (a term popularized by Nassim Nicholas Taleb) gained traction in the 1990s, recognizing that some events are fundamentally unpredictable. As complexity increases, the chances of the unknown unknown or “Black Swan” event increase.

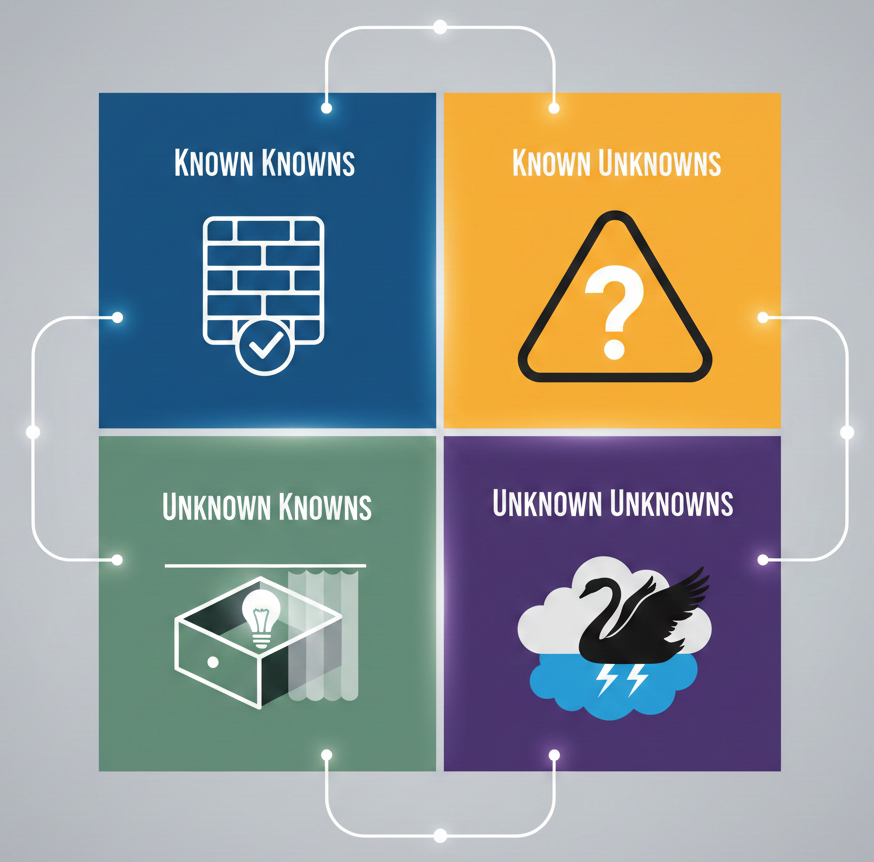

Defining the Quadrants

Known Knowns: Facts and information that we can plan around

Known Unknowns: Identified risks and uncertainty that we’re aware of but don’t have a solution for (yet)

Unknown Knowns: Knowledge that exists somewhere but is not being utilized. These can often be unlocked through cross-functional reviews, documentation, and knowledge base search. Another engineer may have already solved your issue previously

Unknown Unknowns: Risks and uncertainty that we’re not aware of

The Trap of the “Low-Hanging Fruit”

Identifying the known unknown is a critical part of planning projects and tasks. This concept isn’t only for project managers. When an engineer is assigned a task, they should identify any unknowns up front. These are the most likely to explode. Typically, our goal isn’t to complete our tasks perfectly on the first pass. Instead, the goal is to learn quickly, adapt to findings, and minimize the negative impact if your assumptions are incorrect. Conversely, a deadly term I’ve heard people use is “low-hanging fruit,” which refers to tackling the tasks that are easiest, and should trigger warnings. We must train ourselves to resist always deferring to the low-hanging fruit trap and instead prioritize the mitigation of our known unknowns.

Real-World Example: Handling Connectivity

Imagine you’re developing a video stream for a mobile application. A known unknown might be how performant the system is under poor connectivity conditions. The low-hanging fruit would be developing the video player into your app and playing a static video in your player to show working video functionality. You then decide it’s time to develop the streaming aspect and follow with testing your stream and playback under poor network conditions.You discover the performance is poor and decide your video streaming mechanism isn’t suitable. Now, you have to start your search for a solution that handles poor networks. The problem is you’re 6 days into your 6-day task and discovering your solution will not work.

A better approach is to prototype your video stream solution using as many off-the-shelf crude mechanisms there are to prove that your video solution can withstand poor connectivity conditions. You don’t even need it to be on a mobile device. Perhaps there’s a desktop solution that already implements the functionality you’re expanding into the mobile space, and all you need is your laptop and a poor network to prove your solution. It could be as little as a day to make that important discovery instead of finding out 6 days in.

Confronting the "Unknown Unknown"

The unknown unknown is impossible to identify by nature.Everything is going well, and suddenly an event that was not anticipated occurs. However, the strategy for handling these “Black Swan” events is the same as mitigating the known unknown. We need to find a way to learn fast and adapt.

Real World Example: The Unknown Unknown

Contriving an unknown unknown is difficult. Let's look at a different scenario involving an authentication system. Our authentication system allows for third-party integrations. One such integration is an application that periodically synchronizes the user’s information in bursts of communication. These bursts of communication cause our well-secured authentication service to block the authentication calls because they hit our rate limits, which protect against Denial-of-Service attacks (DDoS). It wouldn’t be possible for us to predict the behaviors of all applications that might use our service. The first part of mitigation would be to systematically identify the cause of the authentication failures using logging mechanisms for the affected users. Once we’ve identified the cause, a strategy for handling the authentication failure is now a known unknown. Our mission becomes a series of prototypes to turn our known unknowns into known knowns.

Don’t Fear the Unknown, Mitigate It

We cannot plan for every specific outcome, but we can plan for adaptability. The "low-hanging fruit" trap promises us quick progress but often leads us into a dead end where our assumptions fall apart. By attacking the unknowns first—through rapid prototyping and immediate risk identification, we strip the "Unknown Unknowns" of their power. Don't wait for the system to break to learn how it works. Hunt for the risks, ignore the easy wins, and build your resilience before you build your features.